Okay, let’s talk Borderline Personality Disorder.

It’s the ugly stepsister of mental health diagnoses, stigmatized by clients and professionals alike. It’s also horribly named, unfairly maligned, and deeply misunderstood.

So what are the stereotypes? Glenn Close in Fatal Attraction, emotional blackmail, manipulation — it’s not pretty. And while grains of truth exist in the outward expressions of the behaviors of BPD, once we learn what they are actually about, we see that they serve to mask a very different underlying picture.

The DSM-5 Diagnosis: A List of Semi-Related Traits

Below, I have rewritten into layperson’s terms the DSM-5 diagnostic checklist for a BPD diagnosis (if you want to read the full clinical-ese, click here).

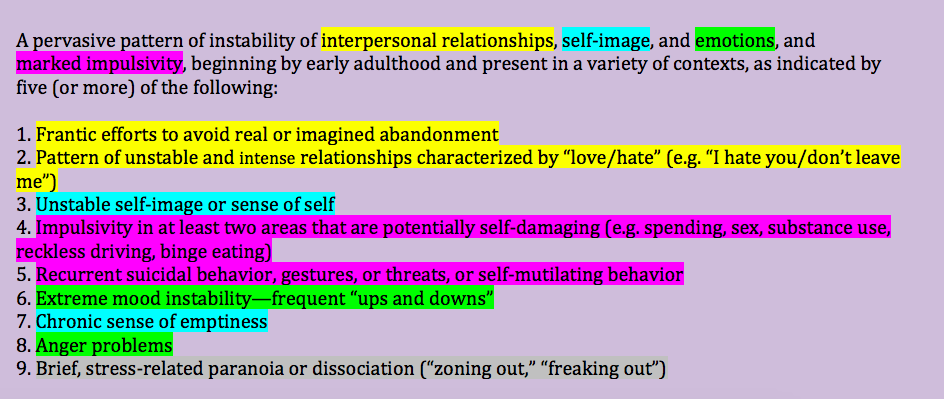

Looking at the DSM checklist, BPD does not seem to make much sense. It is basically a list of nine semi-related traits or symptoms, at least five of which are required for a full diagnosis. I have highlighted different types of symptoms in different colors to make more sense of it, but overall, it reads like an only-semi-related grouping of traits. The symptoms range from self-image problems (blue), to interpersonal chaos (yellow), to emotional reactivity (green), to impulsive behavior (purple), to thinking problems (gray). Nothing seems to fit together into a coherent whole.

Here is a list, in layperson’s terms, of the DSM-5 criteria for BPD. I have color-coded criteria to better group them together, but it still seems fairly arbitrary.

When we look at BPD from its biosocial origins, however, this semi-random list makes a lot more sense. (This view of BPD, by the way, comes primarily from Marsha Linehan’s biosocial model with some of my own thoughts and language thrown in.)

The Biosocial Model of BPD

Like people with any mental health issue, people with BPD tend to start off with certain biological vulnerabilities. In this instance, they tend to be “sensitively wired.”

Biological vulnerability: Dandelions vs. Orchids

Some people (orchids) are born more sensitively wired than others (dandelions). This isn’t good or bad; it just is. And when these orchids, who need very specific conditions to thrive, grow up in environments that don’t validate that sensitivity, problems can occur. To be clear, an invalidating environment doesn’t have to mean abuse or neglect. It can be as simple as a poor fit between parent and child, or too many kids and not enough time or energy to pay attention to the sensitive child’s needs. (To learn more about sensitive wiring, you can check out this page of my website.)

For example, let’s consider “Silvia,” who grew up in a family with four kids and a single parent working two jobs. A sensitively wired child, Silvia felt the world intensely, savoring the beauty of every rainbow and sunset, and grieving over the death of a butterfly. This made her different from her siblings. When she reacted in normal ways to her sensitive wiring, there was no time or energy to attend to her very specific needs, so she was brushed aside, told she was overreacting, or called names (like “crybaby” or “drama queen”). Over time, she started to believe what she was told — that she was “too sensitive” — rather than being just right for who she was. She started to question and judge her own emotions, experiences, and even realities.

Effects of invalidation over time

Deprived of adults in her life who could help guide her through her intense experiences, Silvia began to find ways to deny and numb her feelings. She would gorge herself with chips and sweets during the night when nobody was around. She started to pinch herself and eventually find more dangerous ways to self-injure in order to feel physical pain instead of the emotional pain that she couldn’t understand (after all, she learned that she wasn’t “supposed” to be feeling it — she was simply being “overdramatic”).

In school, what might feel to other kids like “just teasing” felt intolerable to Silvia, and she didn’t have the support at home to help her manage it. She worked extra hard to guard the friendships she did have, always fearful that they may turn against her, and she developed a jealous nature. Her clingy behaviors started to push her friends away, reinforcing her fears of losing them.

By early adulthood, Silvia’s relationships were intense and stormy. She had one or two close friends at a time. If she learned one friend was going out with another friend without inviting her, she would either “blast” the friend out or not talk to her for days, as the pain of the slight felt like too much to handle. She frequently thought people “hated” her. She felt alone and empty, and found it very difficult to be by herself.

Like many orchids living in invalidating situations, Silvia found it easier and easier over time to get emotionally dysregulated (i.e., really upset), and harder and harder to return to a calm baseline. She used behaviors to try to cope with the painful emotions — in this case, abusing food, self-harm — that worked in the moment to make the feelings go away but made her feel worse about herself in the long run. This had a ripple effect into other areas of her life — her difficulty managing rejection made it intolerable to think of losing a friend, so she clung on to the point of ruining those very friendships. Her sense of self was affected by the chronic emotion dysregulation and chaos. Her eating issues increased her alienation from her body. All of this fed on the initial emotion dysregulation and created a snowball effect.

Silvia demonstrates an example of someone with BPD. The biosocial model shows how BPD can develop when an orchid child grows up in an invalidating environment and over time develops severe difficulty with emotional dysregulation.

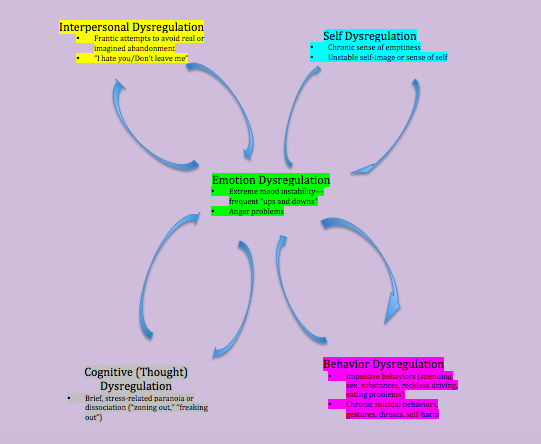

Here is a diagram (with the same colors as above) that explains this view of BPD:

Here is a diagram of BPD symptoms with emotion dysregulation at the center. Notice how the arrows go both ways, with the emotion dysregulation causing the other symptoms, which in turn increase the emotion dysregulation, creating a snowball effect.

Make more sense now? It’s all about emotion dysregulation! The other “dysregulations” can actually be seen as desperate attempts to try to make the pain go away. The behaviors and symptoms may work in the short run, but in the long run, they backfire and add to the emotional chaos.

So why the stigma?

Unfortunately, there is stigma even in the mental health field around BPD. In fairness, as a clinician, it can range from unpleasant to terrifying to have your client launch into verbal attacks or to engage in self-harm or threaten suicide. That said, the clinical community is largely undertrained in understanding what BPD is about.

Rather than seeing people with BPD as “manipulative,” it helps to understand them as emotional burn victims. Think of Silvia’s friend canceling plans at the last minute and Silvia threatening to hurt herself if the friend doesn’t come over to her home that very moment. If we didn’t understand it, we’d say she was trying to manipulate the friend.

However, if you’ve ever been around someone with a very severe burn, you know you could just walk past them and they can scream in pain. Are they trying to manipulate you? No — they are actually in pain. They literally have no skin and their nerve endings are exposed in such a way that the moving air currents make them scream in pain.

Same with someone with BPD, only they have no emotional skin. Something may happen that may seem like no big deal to someone else — like Silvia’s friend canceling plans — but the pain is as much to them as it is to the burn victim because they have no emotional skin. They may “scream” in pain like Silvia does — by engaging in self-harm, going into a rage attack, “freaking out” — in whatever way is available and familiar to them.

They are no more trying to manipulate you than the physical burn victim; they just don’t have the skills to deal with the emotional pain that can feel life-threatening in the moment. What may have dysfunctional and even dangerous results is often a frantic attempt to make the pain go away. It may feel manipulative to others, as the behaviors can have the effect of drawing others into the cycle, but that’s not the actual intent of what is going on.

In this case, Silvia is likely behaving in the only way she knows how in the moment to make the pain go away. She probably doesn’t want to engage in self-harm — frankly, who would? — but knows no other way. She believes she needs, however, some way to kill the immediate pain and doesn’t know how, because she truly believes in the moment that it is life-threatening. (What Silvia really needs is compassionate, validating treatment, with appropriate limit-setting and teaching of new skills.)

Understanding that someone doesn’t mean to manipulate does not mean that it isn’t important to have limits and boundaries or to turn someone’s care to professionals when it is warranted (that is actually the most loving thing you can do at times). Silvia’s friend would be wise to set some strong limits with her, as she is not responsible for Silvia’s behavior. (For some tips on dealing with a loved one living with BPD, click here.) You can set limits and still have compassion that the person is attempting to manage their pain rather than manipulate.

Additionally, the clinical community overall needs better education and training in treatments such as DBT, which are shown to help people get better.

Why the name?

Ah, yes. The name. The term “Borderline Personality Disorder,” can spark many misconceptions:

- “My personality is wrong.”

- No. It’s not. A “personality disorder,” as per the DSM, is a technical term that describes an “enduring pattern” throughout adulthood of “inflexible and pervasive” internal and behavioral traits that cause distress and impairment. Of course, calling it a “personality disorder” couldn’t be MORE invalidating…. How about emotional dysregulation disorder?

- “I have multiple personalities.”

- No, you don’t. This comes to mind for people because it sounds like the old diagnosis of “multiple personality disorder.” It’s not, though.

- “What’s with the ‘borderline’ thing?”

- Yeah, that doesn’t really make sense either, does it? Back in the days of Freud, people with BPD were seen as “on the borderline” between neurosis and psychosis. That is because at times, when people with BPD are emotionally dysregulated, it’s possible to have cognitive distortions to the point where they can seem psychotic even though they are really not. Hence, “borderline.” I know, lame, right?

What’s the takeaway?

People with BPD are not bad, crazy, or trying to manipulate. They are people in pain doing the best they can with the skills they have to try to make it not hurt so much. It is possible, though, to learn new ways of managing the pain and living in less pain. The amazing thing about being sensitively wired is that once you learn new ways to deal with your sensitivity and live in less pain, you can also experience beauty in the world in ways that less sensitive people can only dream of. People can and do get better!

If you or a loved one are struggling with BPD, find a treatment team who will discuss your diagnosis with you. Ask them about their experience treating people with BPD. Learn about BPD stigma and fight against it.

Recovery is real.

This information is not a substitute for therapy. If you are experiencing a clinical emergency, go to your nearest emergency room or call 911. I am available for online psychotherapy for anyone in New York State. If you are interested in scheduling a free consultation, you can contact me through my page.

For further reading:

- The NEABPD is an organization dedicated to BPD awareness, education, and research and is an excellent resource.

- BPD Demystified is a resource-filled site run by a psychiatrist whose sister lived with BPD.